Examining data broker Equifax’s relationships with millions of employers

Justin Sherman

August 24, 2022

Equifax is one of the largest data brokers in the United States. In 2021, according to its report to investors, Equifax made $4.923 billion, a 19% increase over 2020. The company’s data brokerage offerings are wide-ranging: for example, Equifax advertises that it has gathered a large amount of data on individuals, including data on 45% of the nations’ assets spanning “digital targeting segments” including wealth, financial durability, online interest, investments, student loan, retail banking, ability to pay, communications, travel and leisure, and more.

Equifax’s current “digital targeting segments” webpage says it “enables segmentation of consumers,” and it lists, as examples, an “affluence index” (“use Affluence Index Digital Targeting Segments,” it says, “to better reach online consumers that likely have the discretionary funds to spend on your products or services—or to save or invest for the future”); a “financial cohorts” segment (which it says “helps marketers to better understand the estimated financial/behavioral characteristics of households in target clusters”); and an “economic spectrum” segment (which it says “ranks and scores US households based on a measure of their total income and their relative share of total estimated US spending”). Within its “auto credit segments,” Equifax describes profiling whether a consumer target population is “very likely to obtain an auto loan or lease and have poor-very bad credit.”

Though, it doesn’t end there. Equifax also has relationships with another category of often overlooked entities: millions of American employers.

Created in 1995, Equifax’s service The Work Number monetizes employees’ information, primarily (as far as one can tell) for income verification purposes. By 2013, according to journalist Bob Sullivan (now affiliated with Duke’s Sanford School), The Work Number reportedly had 190 million employment and salary records on Americans. Joel Winston at Fast Company published a story in 2017 reporting The Work Number had expanded to more than 296 million employment records in its database—from CEOs to interns, from Fortune 500 companies to 85% of the federal workforce, from “entire state governments and agencies” to “courts, colleges, and thousands of small businesses nationwide.” In July 2021, Intuit told 1.4 million small businesses it was going to share their payroll information with Equifax by the end of the month if they did not opt out. As of April 2022, Equifax states that it has “over 535 million active and historic records from 2.5 million contributors to The Work Number.”

Monetizing employee information is, once again, just one component of Equifax’s overall data brokerage business. On its website, Equifax’s privacy policy (as of June 2022) says “in the preceding 12 months,” it has “disclosed the following categories of personal information to third parties for business purposes”:

- “Identifiers” — to advertising networks, business process outsourcing providers, creditors/collection agencies, consumer data resellers, data analytics providers, data brokers, data processors and storage providers, Equifax group companies in the United States, financial institutions, government agencies and contractors, identity verification companies, insurance carriers/agencies/partners, internet service providers, marketing companies, operating systems and platforms, parties to litigation, retail merchants, social networks, and utility providers;

- “Personal information categories listed in the California Consumer Records statute (Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.80(e))” — to the same set of entities in the above bullet;

- “Protected classification characteristics under California or federal law” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”);

- “Commercial information” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”);

- “Biometric information” — to identify verification companies;

- “Internet or other similar activity” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”);

- “Geolocation data” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”);

- “Sensory data” — to business process outsourcing providers and Equifax group companies in the United States;

- “Professional or employment-related data” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”);

- “Non-public education information (per the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C. Section 1232g, 34 C.F.R. Part 99))” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”); and

- “Inferences drawn from other personal information” — to the same set of entities in the first bullet (“identifiers”).

Equifax’s privacy policy explicitly states that “we do not sell personal information of consumers under the age of 16 years old.” The company’s own literature alone demonstrates the immense amount of data it gathers on individuals, “infers” about individuals, and monetizes. As highlighted above, this includes “professional or employment-related data” that Equifax has provided to a wide range of organizations, from social networks to government agencies.

After looking further into The Work Number, a curious finding stood out vis-à-vis Equifax’s internal handling of data on American workers. When The Washington Post published a story in March 2022 on The Work Number—highlighting that tech company employees were upset their employers were sharing their data with Equifax—the Post quoted a comment from an Equifax executive. In the Post’s words:

“Data shared with the Work Number is not passed on to other parts of Equifax, and is stored completely separately, said Joe Muchnick, senior vice president and general manager of the company’s employer services and talent solutions division. Banks, loan officers and prospective employers can only access someone’s data with their express consent, he said.”

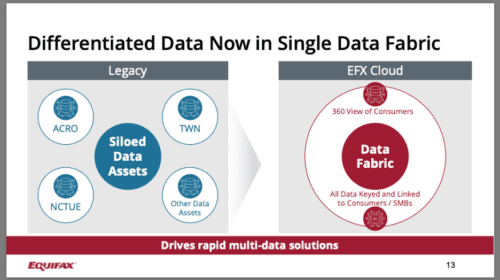

This appeared to suggest that when Equifax gathers data from employers on their employees—including sensitive information about those people’s incomes—it keeps the information firewalled from other parts of the Equifax data brokerage business and does not monetize it outside of income, employment, and identity verification services. However, Equifax’s Investor Day 2021 presentation, from November 2021, contains the following graphic on a slide:

This appeared to suggest that data from The Work Number (identified on the left of the slide as “TWN”) is integrated into a “360 View of Consumers” as part of Equifax’s “Data Fabric.” (There are other slides in the presentation that also appear to suggest that data collected on American workers is used beyond The Work Number itself, though this slide was the clearest in that suggestion.) All told, it at least appeared that the Equifax presentation to investors contradicted Muchnick’s comment to The Washington Post in March.

Upon examination of this information, I emailed several questions to Equifax’s press inquiry email address. For informational purposes, the entire set of questions and Equifax’s full responses are below, completely unedited—followed by a discussion and analysis. Equifax claims that the above understanding of the slide deck is not accurate and that Equifax does not use or monetize data related to employees and The Work Number beyond that service itself. It did not provide any additional documentation in response to the below questions. Additionally, Equifax has not yet responded to the two subsequent questions I sent in reply to their initial responses below. If Equifax does answer those questions or provide more information, I will update this post accordingly.

—

Question: What is Equifax’s process for acquiring data for TWN?

“Equifax has relationships with 2.5 million employers and payroll partners nationwide that contribute income and employment data to The Work Number database, concurrent with each payroll cycle. Information in that database is provided by, or on behalf of, individual employers, and is reported out by The Work Number as the information is received from those employers.”

Question: What, if any, contractual controls does Equifax put in place or have put in place as part of that data acquisition?

“Data contributed to The Work Number belongs to the employer. Equifax use of the data is determined by the employer’s requirements and is also done in accordance with the requirements of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).”

Question: What, if any, notice does Equifax provide to individuals about the acquisition of their information and the uses of, and controls on the subsequent uses of, data acquired for TWN?

“We provide employers and payroll providers with materials to share with their employees regarding the benefits of The Work Number. Additionally, we encourage individuals to visit employees.theworknumber.com, where they may learn how to obtain their Employment Data Report, which is a full disclosure of any and all information The Work Number has regarding that individual, along with a list of every entity that has requested such information over the past two years. Individuals are able to dispute any inaccurate or incomplete information here, and they can also freeze their Employment Data Report here.”

Question: Does Equifax completely isolate TWN data from all of its other databases and data uses internally?

“TWN data is isolated and is never commingled with other databases.

Equifax maintains data in a data fabric that allows for separation of data and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. The publicly available recording of our Investor Day provides additional context on the referenced slide. Within that slide, The Work Number is listed as a representation of a type of dataset maintained by Equifax. The 360 view is outlined as a concept (not a product) where multiple datasets - all maintained separately - can be accessed according to each dataset’s specific rules in a more efficient, more nimble manner via our data fabric, in accordance with strict governance and security standards.”

Question: Does Equifax monetize data from TWN, or metadata or other insights from TWN data and the TWN process, in any way other than employee verification of individuals’ employment information?

“Consumer employment and income data is not sold for additional purposes beyond the scope of the FCRA, nor is it used for marketing.”

—

Equifax did not provide any documentation to back up its assertion that data associated with The Work Number is not used beyond that service. The company has also not yet responded to my two other questions: “What kind of technical measures, including technical access controls, are used to isolate the data? Are there any administrative controls as well (e.g., internal compliance checks) used to ensure that commingling of TWN data with other data does not occur?”

It is, of course, possible that Equifax gathers data from employers as part of The Work Number and does not use that information for any other purpose. Though worth a deeper legal examination, Equifax’s comment about the Fair Credit Reporting Act may support this hypothesis—indicating that it may treat all data related to employees as more sensitive due to its obligations as a credit reporting agency under the FCRA. Nonetheless, Equifax’s lack of additional documentation to back up its claim means there is not enough information to make a conclusive judgment.

There is also an open set of questions about whether companies that broker data (a) have any kind of standardized set of controls, (2) what those controls look like, (3) if those controls are enforced in practice, and (4) how those controls are enforced in practice. For example, my colleague Alistair Simmons and I recently published an article about the Justice Department prosecuting three data brokers across 2020 and 2021—because each of them knowingly sold data on Americans, for about a decade each, to criminal scammers. Large data broker Epsilon had employees, per the charging documents, who were fully aware of the fact that their “clients” were scammers looking to steal from “elderly and vulnerable” Americans, yet those individuals sold the information anyway. Another data broker, KBM, had internal controls in place to vet potential data buyers—but when one individual at the company followed and enforced the controls, two other individuals overrode the controls and sold people’s information to scammers anyway. These kinds of stories at least raise the question, if not suggest, that data brokers with controls on paper may not actually enforce those controls in practice.

Many other issues persist and demand further study. Employers sharing employees’ information comes with its own unique set of risks and harms. In August, for instance, The Wall Street Journal uncovered that Equifax had provided inaccurate credit scores on millions of US consumers—sometimes off by 20 or more points—during a three-week period earlier in 2022. This harms any number of individuals, who may not even be aware their credit scores are wrong, and who may have missed the opportunity for true recourse by the time the error is corrected in the database, because their loan application or apartment lease application has already been rejected.

There is also a question of the position that consumers are put in when they are forced to have their data collected, monetized, and shared in order to access employment opportunities. Companies are quick to cite individuals’ “consent” in these kinds of situations—as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) states with respect to the Fair Credit Reporting Act, “a consumer reporting agency may not give out information about you to your employer, or a potential employer, without your written consent given to the employer”—but a market and regulatory environment in which workers are essentially powerless to the sharing and monetization of their own information is not one in which that consent is full, informed, and freely given.

Among many other practices in the data brokerage ecosystem, the use of employees’ information demands further study and policy attention.

—

Justin Sherman (@jshermcyber) is a senior fellow at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, where he leads its data brokerage research project.